- By evaluating a big 177-year-old colonial map with trendy satellite tv for pc photographs, researchers discovered that the Nilgiris have misplaced practically 80% of their grasslands since 1848.

- Century-old chook specimens and naturalists’ diaries guided scientists again to the very websites the place these species had been as soon as recorded, revealing that just about 90% of grassland birds, together with the Nilgiri pipit, have sharply declined.

- The research exhibits how colonial insurance policies nonetheless form right now’s ecosystems and why preserving historic information is significant to understanding the current.

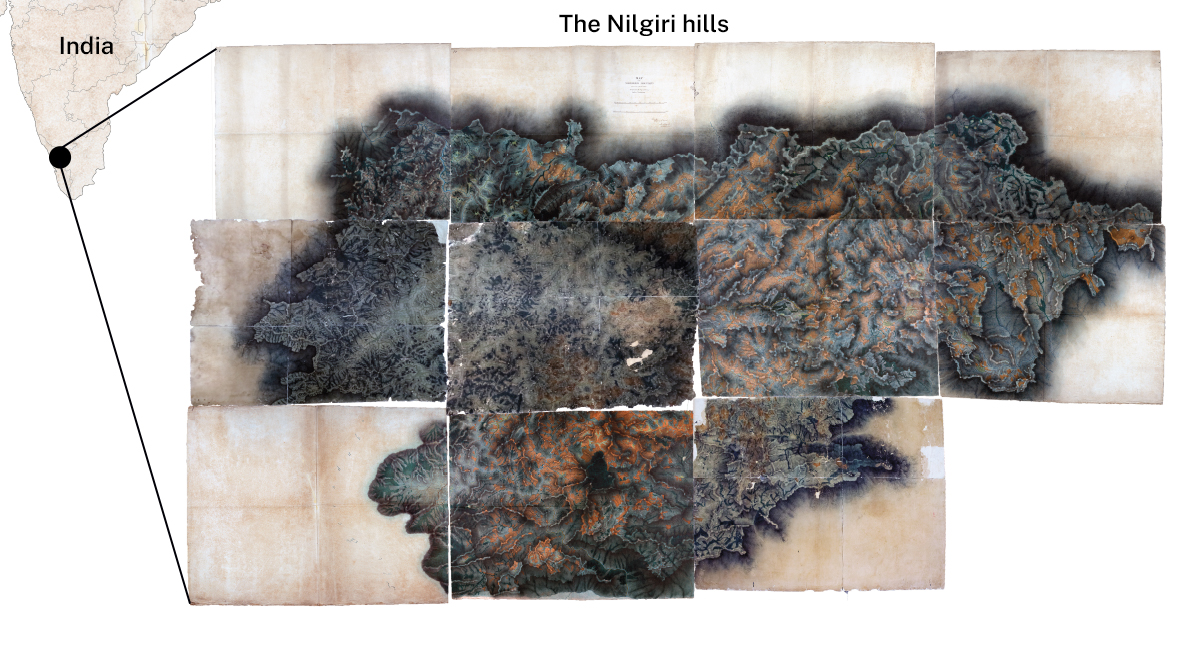

In a library in London, researchers fastidiously unfolded a fragile 177-year-old Indian map throughout the ground like an enormous jigsaw puzzle. In one other museum on the outskirts of London, researchers scanned by rows of century-old Indian chook specimens with handwritten labels neatly organized in drawers. Collectively, these fragments helped the group inform a trendy story: how British colonial-era insurance policies triggered the collapse of the Nilgiris’ grasslands and the birds that after thrived there.

Excessive within the southern Western Ghats, the Nilgiri hills, dwelling to hill stations like Ooty and Coonoor, and a backdrop for Bollywood movies, as soon as hosted an expansive, placing mosaic of evergreen forests known as sholas and rolling grasslands. These montane shola-grasslands, about 20,000 years outdated, assist threatened biodiversity, channel water into rivers, and maintain native cultures.

However in lower than two centuries, a lot of this panorama has been erased. The grassy expanses that after stretched for kilometres are actually carpeted by tea, eucalyptus, pine, wattle, and others, vegetation launched by the British settlers within the 1800s.

Earlier satellite-based research estimated that montane grasslands throughout the Western Ghats have declined by about 66% in simply 4 a long time attributable to unique timber and their invasion. However by revisiting colonial information, a July 2025 research by a global group of 10 establishments reveals an extended arc.

Since 1848, the Nilgiris have misplaced practically 80% of their iconic grasslands, and virtually 90% of grassland-dependent birds have declined too.

The Nilgiris: then and now

“I’ve all the time been fascinated by historic knowledge and what that may inform us about environmental change,” says Vijay Ramesh, lead writer of the research and a postdoctoral fellow on the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. “A part of the colonial legacy was the creation of maps and specimens collected as a part of looking expeditions or systematic surveys.”

Working within the Nilgiris since 2016, Ramesh turned conscious of Captain John Ouchterlony’s first systematic map of the area from 1848 and dug by archives to seek out out extra. He tracked it down throughout establishments: two sheets within the Tamil Nadu State Archives, seven within the British Library, and one nonetheless lacking. “We fastidiously unfurled them and laid them on the ground like a ten×6 ft jigsaw puzzle. I climbed a stool to get a large view and take pictures,” recollects Ramesh.

Utilizing an accompanying 1848 booklet, research co-author Amrutha Rajan manually digitised the map, tracing several types of land, after automated instruments failed in differentiating the illustrated particulars within the older map. The ensuing map, born out of a laborious course of that spanned 1.5 years, Ramesh says, was ground-truthed with long-term Nilgiris residents — a dentist, a non-profit director, a reverend, and plenty of extra — all passionate and educated in regards to the area.

When put next with 2018 satellite tv for pc imagery, the adjustments had been stark. In 1848, grasslands lined about 1,000 sq. kilometres, roughly 1.6 instances the dimensions of Mumbai. By 2018, solely 200 sq. km. remained. Intermediate maps from 1910, 1973, and 1995 confirmed that almost all of this conversion occurred underneath the British rule and continued after independence.

The British officers propagated a false impression that indigenous communities deforested the panorama, famous earlier research. From the 1820s onward, British officers dismissed grasslands as “wastelands” and planted over 40 unique tree species to “restore” the land and for business use. Right now, their legacy endures: invasive unique species proceed to unfold into the remaining grasslands — picturesque greenery that masks ecological injury.

Studying useless birds and diaries

Whereas one a part of the group deciphered the maps, one other sifted by museum collections to construct a historic image of Nilgiris’ chook species and the place they had been discovered.

Researchers visited museums in India, the UK, and the USA, with most information drawn from the Pure Historical past Museum at Tring, close to London. These included specimens from the primary systematic ornithological expedition in 1881, led by William Davison.

Additionally they pored over journals, letters, and diaries: from Margaret Cockburn, an artist and ornithologist within the Nilgiris; Stray Feathers, the ornithological journal run by A.O. Hume, founding father of the Indian Nationwide Congress; the Journal of the Bombay Pure Historical past Society; and others.

“We solely picked places the place we might pinpoint and resurvey,” explains Ramesh. “For instance, if a chook document mentioned ‘Western Catchment of Mukurthi Nationwide Park’, we knew precisely the place to look once more. If it mentioned ‘Nilgiris,’ we dropped it.”

Utilizing information from 1850 to 1950, the group recognized 85 chook species throughout 42 websites, mapping them on each outdated and new maps. Over a number of months and early mornings in 2021, they returned to these precise places for resurveys. Some had been nonetheless grasslands; others had turn out to be plantations and even city settlements. At every website, they logged each chook seen or heard by systematic counts.

To make the previous and current comparable, the group used statistical fashions that put outdated specimen counts and trendy surveys on the identical scale, revealing which species rose or fell in relative abundance.

Losers… and winners?

The outcomes of the research echo the state of grassland birds throughout India and the world. Almost all grassland specialists collapsed, with the Malabar lark and Nilgiri pipit, species distinctive to the Western Ghats, exhibiting the steepest declines. “Mukurthi Nationwide Park, the place the grasslands are nonetheless intact, appears to be one of many final remaining strongholds of the Nilgiri pipit and different grassland birds,” says Ramesh. An exception was the pied bushchat, which held regular by adapting to tea plantations and different open habitats.

Forest birds confirmed a blended image: about half declined, whereas the remainder remained secure and even elevated. Species such because the black and orange flycatcher additionally use timber plantations, very similar to pure forests. However Ramesh cautions: “It’s important to have a look at this transformation within the context of Nilgiris and never as a sign of plantations being a substitute for forest habitats.”

Generalist birds such because the large-billed crow and red-whiskered bulbul, in the meantime, have thrived, capitalising on the reworked panorama.

Again to the longer term

The researchers additionally tried to evaluate the influence of local weather. They tried tapping into historic rainfall and temperature information from the 125-year-old United Planters’ Affiliation of Southern India, however couldn’t comply with by. Whereas detailed knowledge proved elusive, co-author Pratik Gupte analysed coarse information from the India Meteorological Division from 1870 onwards. These information confirmed that month-to-month temperatures within the Nilgiris are actually a couple of diploma hotter than they had been 150 years in the past.

Past the ecological findings, the research additionally underscores the hidden worth of archives in understanding environmental change. Venkat Srinivasan, head of Archives at Nationwide Centre for Organic Sciences (NCBS), a public amassing centre for the historical past of science in up to date India, sees extra scope for using archives for ecology and different fields, drawing from historians. “Understanding archives, accessing them, and touring to those archives are legitimate challenges, however they’ve options. Nevertheless, the primary and largest problem for a researcher may be in figuring out that this world (tapping into archives) exists and that it may very well be a key strategy to their analysis,” he explains.

By combining colonial maps, museum specimens, naturalists’ area notes, and trendy surveys, the research creates one of many clearest long-term photos of how land-use change reshaped ecosystems within the Nilgiris. The strategy, Ramesh notes, may very well be tailored somewhere else with colonial historical past and information, emphasising the necessity to digitise and protect historic information that would disintegrate over time.

However whilst extra archives endure digitisation, Srinivasan cautions towards the false consolation it gives. Digital entry is distinct from digital preservation, which calls for sustained effort to supply archival-quality copies, guarantee dependable entry, safe knowledge, and cross-link materials inside catalogue metadata. A list is a descriptive instrument that helps customers find and make sense of supplies. “If the digitisation isn’t first preceded by constructing and sustaining a strong archival catalogue, the worth is misplaced,” he notes.

For Vasanth Bosco, founding father of Nilgiri-based Upstream Ecology and a restoration practitioner for over 12 years, such science-backed findings reassure the necessity to preserve montane grasslands within the shola-grassland ecosystem and likewise perceive the location to take particular approaches. “Science helps form coverage, however typically science is just too sluggish, given the tempo of change and dynamics on the bottom. There’s a lag that we have to tackle to implement the ends in quick administration practices,” he provides.

Conservation insurance policies overlook grasslands. They’re typically focused for tree-planting schemes, although research present they’re essential for biodiversity, carbon storage, and water regulation. “In India, as in different former European colonies like South Africa and Madagascar, open pure ecosystems equivalent to grasslands are undervalued and thought of wastelands,” says Ramesh.

“However there’s big scope and profit in restoring grasslands,” says Bosco, recollecting the sight of a Nilgiri pipit in a small grassland patch his group restored amidst “a sea of tea” in a area reworked over centuries. “Nevertheless it hasn’t gained reputation and funds.”

Banner picture: Yellow-browed bulbul specimens collected from the Nilgiri hills within the 1800s on the Pure Historical past Museum at Tring, England. Picture by Vijay Ramesh.