- Rohini Balakrishnan has spent a long time listening to bugs, uncovering what their calls reveal about behaviour, communication, and evolution.

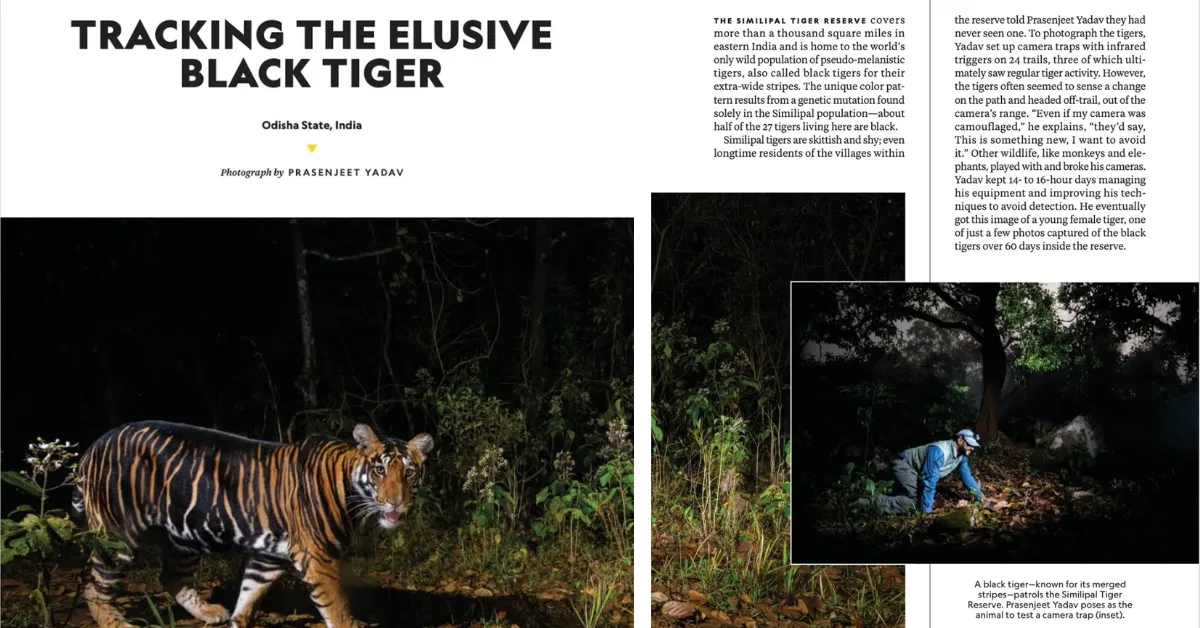

- On this interview with Mongabay India,

she highlights the potential of mixing audio archives, machine studying, and citizen science to bridge crucial data gaps within the acoustic information for bugs. - As acoustic monitoring features floor globally, she displays on what’s lacking in India and why insect sounds deserve greater than being dismissed as background noise.

Bugs could also be small, however their acoustic worlds are huge and sophisticated. Rohini Balakrishnan has spent her profession listening in. A professor on the Indian Institute of Science in Bengaluru, she leads the Animal Communication and Bioacoustics Lab.

From campus labs to discipline websites on town’s outskirts and deep within the evergreen forests of Karnataka’s Western Ghats, Balakrishnan and her crew research the causes and penalties of animal behaviour by specializing in their calls. These sounds provide a window into insect evolution, communication, and ecosystem change.

On this dialog with Mongabay India, Balakrishnan displays on what insect calls can reveal about species and their habitats, the challenges of learning such a various group in India, and the instruments that will assist overcome them. As acoustic monitoring features traction globally, she highlights each its potential and its pitfalls. She explains why insect calls are way over simply “noise”.

Mongabay: What are some insights you’ve discovered about bugs simply by listening to them?

Rohini Balakrishnan (RB): Systematics and species delineation often depend on visuals: museum specimens, photographs, and many others. However many bugs, particularly nocturnal ones like crickets, are visually cryptic. They appear an identical, but are literally totally different species and have distinctive acoustic indicators. Whenever you shift from the visible to the acoustic area, distinct species grow to be evident.

Listening has all the time pushed my analysis. Each query started by strolling and listening. You hear this big vary of sound frequencies and marvel: who’s producing what? How are animals managing to speak in such a loud setting, say, to a feminine of their very own species when everybody is asking on the identical time?

We began monitoring calls, who’s calling, when and the place, over 15 years. We even constructed a 3D acoustic mannequin of a rainforest. What appears like cacophony to us typically dissolves into silence when measured alongside the appropriate axes. Both animals have solved the issue of interference, or perhaps the issue by no means existed the best way we thought.

Mongabay: Your work on bat and bug relationship additionally proved some assumptions improper. Are you able to inform us in regards to the work and what you discovered?

RB: That began with listening too. In Kudremukh, I used to be making an attempt to trace a calling insect at midnight. I turned off my torch since I discover it distracting once I’m making an attempt to localise sound with my ears. One thing brushed previous my face. I turned on the crimson mild and noticed a bat catching a calling insect.

It sparked a query: these crickets are making loud, broadband calls, why hasn’t there been evolutionary choice in opposition to that, particularly within the genus Mecopoda (bush crickets)? Within the neotropics, research confirmed that bat predation could have led to shorter or vibrational calls in crickets. However we weren’t seeing that in India.

So we requested: How possible are bats to strategy and seize these calling crickets?

First, we recognized the predator, the lesser false vampire bat, by discovering cricket wings underneath bat roosts in deserted homes. We’ve studied it for years and located counterintuitive outcomes. Males (crickets) name and females are silent, So you’ll assume that males are at excessive danger, as a result of they’re those producing loud calls. However females have been eaten extra typically!

In enclosure experiments, we examined how typically bats approached calls, flying bugs, and strolling ones. We discovered calling and flying people are approached equally, so that they’re at equal danger.

Mongabay: Monitoring small, nocturnal bugs in dense forests sounds tiring. How do you try this?

RB: Most of this work is finished by my college students, although I’ve carried out it too. There’s no substitute for the human mind in localising sound. You isolate a name, work out its route and peak, and strategy slowly. When you find the insect, you file the decision, catch it, mark it with a non-toxic paint code, and launch it. These species are solitary and don’t keep in a single place, so we spend every week marking each calling particular person in a patch. Then we return to trace calls, utilizing crimson mild so we don’t disturb them. If the insect stays, we briefly use white mild to learn the code. We’re among the many few who’ve carried out this sort of guide monitoring on solitary bugs.

Mongabay: Why is it vital to observe bugs at a panorama degree?

RB: Bugs are highly effective indicators of land use and ecosystem well being as a result of they’re small and extremely delicate to microhabitat and microclimate. However they’ve not obtained sufficient consideration in eco-acoustic research.

Mongabay: Are you able to elaborate on that?

RB: Restoration research typically deal with vegetation or birds. However bugs are all the time current in soundscapes and name throughout a large frequency vary, from beneath one kilohertz to ultrasound.

It’s telling that eco-acoustics papers typically seek advice from insect sounds as “noise.” The sector is so vertebrate-focused that bugs get ignored.

You’ll be able to compute varied acoustic indices from spectrograms, photos that present sound frequencies over time, from audio recordings. However their usefulness is blended, particularly when ground-truthed; for instance, if we ask how the mathematical end result correlates with the recognized variety of vocalising species on the bottom. And most of that work has been on birds, not bugs.

Mongabay: What limits using insect acoustics in biodiversity monitoring?

RB: You need to use recorders to gather soundscapes and create spectrograms. The visible patterns or sonotypes mirror totally different acoustic indicators you hear within the habitat. However to rely species, you want a one-to-one match between every acoustic sample and species id, like we now have for birds. That’s simpler in Europe or North America with fewer species and extra analysis. In India, we’re removed from that.

For bugs, there’s a taxonomic hurdle and we lack elementary acoustic information. Authentic taxonomic specimens are sometimes in European museums. However acoustic species typically look an identical, so even 3D photos of museum specimens aren’t sufficient. You continue to have to see the animal, make a recording, and know precisely who it’s. We did this for about 25-30 species in Kudremukh, however how do you try this for 30,000?

Recorders are low cost now, so we’re accumulating large information. In passive acoustic monitoring, you set out a bunch of recorders and acquire sounds. We want repositories to retailer and reuse this information. What you extract is dependent upon your query.

It’s additionally an enormous information drawback. Machine studying will help, however that you must know what drawback you’re fixing and feed the system the appropriate details about what the sounds are to get something helpful.

Mongabay: Is there a method to hyperlink insect identities to sounds extra effectively?

RB: We want a citizen science motion. Everybody has a cell phone, and whereas the audio will not be high-quality, it’s usable. If folks uploaded photos, sounds, and GPS areas, like on iNaturalist, we might construct that information. The secret is linking a confirmed picture to a sound and site. Somebody nonetheless has to ground-truth it, but it surely’s an amazing begin. In a rustic like India, with restricted funding prioritising documentation, this can be the one scalable resolution. Species communities can change each 50-100 km in India. Figuring out and linking species to sound is a gargantuan process.

We will additionally use museum specimens and machine studying. Utilizing finite ingredient fashions (FEM), we predicted the service frequencies of 9 cricket species precisely. Alternatively, one might deal with soundscapes. As an alternative of figuring out each species, analyse frequency bands or sonotypes as indicators of habitat high quality. Certainly one of my PhD college students is doing this utilizing soundscapes as proxies for ecological well being.

Mongabay: What will we find out about bugs in city environments?

RB: I’m a bit sceptical of the literature on anthropogenic noise and bugs. Most research are correlational, like evaluating bugs close to roads and farther away, and present variations in calls or behaviour. However many different elements could possibly be at play.

Some lab experiments play site visitors noise to bugs. Sure, calling behaviour modifications as noise will increase. However in contrast to birds, bugs don’t exhibit the Lombard impact–they don’t get louder in noise. They may cease calling, and females could battle to seek out mates.

However I don’t suppose lab setups mirror real-world city cricket experiences. I’ve spent years reconstructing acoustic perceptual environments, and we want lifelike and manipulative discipline experiments to check the influence of anthropogenic noise on bugs. Additionally, bugs don’t hear properly beneath one kilohertz. So low-frequency site visitors noise, which impacts birds, won’t have an effect on bugs the identical method. Vibrations may matter extra. However site visitors noise additionally has high-frequency parts, which may overlap with insect calls.

It’s an enchanting topic. I most likely gained’t pursue this additional in my educational profession, however I hope somebody will take it ahead with a unique, extra field-based methodology.

Mongabay: What’s the way forward for insect bioacoustics in India?

RB: Eco-acoustic monitoring is a serious alternative. It’s comparatively low cost, scalable, and will help monitor panorama modifications. International locations like Norway, the UK, and Australia already run nationwide acoustic monitoring networks.

It may well assist in agriculture too. Most pests don’t make loud airborne sounds, however they do produce vibrations, like larvae feeding inside stems. These will be detected with sensors. There’s already promising work on this space.

Mongabay: After three a long time of labor, does it nonetheless shock you the way little we find out about bugs?

RB: I’ve stopped being stunned. Every thing I’ve studied has led to new findings or proven that our easy assumptions don’t maintain. That’s thrilling as a result of it means there’s far more happening.

Hearken to the Wild Frequencies Podcast:

Banner picture: A bat catches a bush cricket. Picture by Saravanakumar.

![Rohini Balakrishnan on why (and the way) we should hearken to bugs [Interview]](https://foreignshoresnrinews.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/RB-768x512.png)