Mehebub Sahana, College of Manchester

The Ganges, a lifeline for tons of of thousands and thousands throughout South Asia, is drying at a charge scientists say is unprecedented in recorded historical past. Local weather change, shifting monsoons, relentless extraction and damming are pushing the mighty river in direction of collapse, with penalties for meals, water and livelihoods throughout the area.

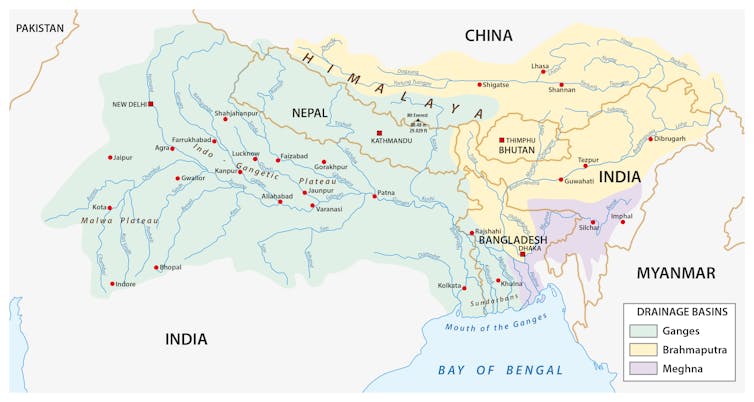

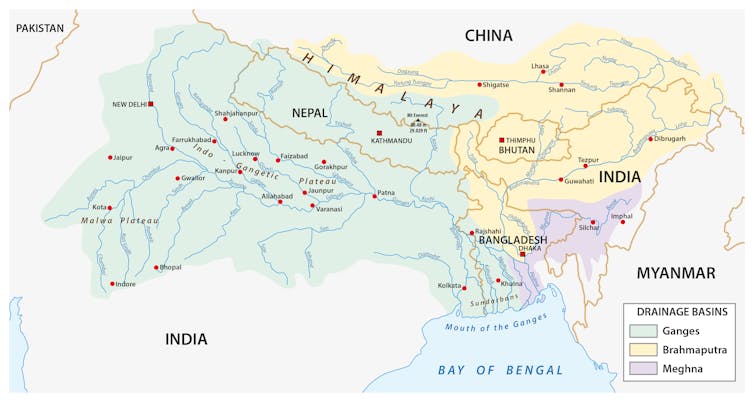

For hundreds of years, the Ganges and its tributaries have sustained one of many world’s most densely populated areas. Stretching from the Himalayas to the Bay of Bengal, the entire river basin helps over 650 million folks, 1 / 4 of India’s freshwater, and far of its meals and financial worth. But new analysis reveals the river’s decline is accelerating past something seen in recorded historical past.

In current many years, scientists have documented alarming transformations throughout most of the world’s large rivers, however the Ganges stands aside for its pace and scale.

In a new examine, scientists reconstructed streamflow information going again 1,300 years to point out that the basin has confronted its worst droughts over the interval in simply the previous couple of many years. And people droughts are properly outdoors the vary of pure local weather variability.

Stretches of river that when supported year-round navigation at the moment are impassable in summer time. Giant boats that when travelled the Ganges from Bengal and Bihar via Varanasi and Allahabad now run aground the place water as soon as flowed freely. Canals that used to irrigate fields for weeks longer a technology in the past now dry up early. Even some wells that protected households for many years are yielding little greater than a trickle.

International local weather fashions have didn’t predict the severity of this drying, pointing to one thing deeply unsettling: human and environmental pressures are combining in methods we don’t but perceive.

Water has been diverted into irrigation canals, groundwater has been pumped for agriculture, and industries have proliferated alongside the river’s banks. Greater than a thousand dams and barrages have radically altered the river itself. And because the world warms, the monsoon which feeds the Ganges has grown more and more erratic. The result’s a river system more and more unable to replenish itself.

Melting glaciers, vanishing rivers

On the river’s supply excessive within the Himalayas, the Gangotri glacier has retreated almost a kilometer in simply 20 years. The sample is repeating internationally’s largest mountain vary, as rising temperatures are melting glaciers quicker than ever.

Initially, this brings sudden floods from glacial lakes. Within the long-run, it means far much less water flowing downstream through the dry season.

These glaciers are sometimes termed the “water towers of Asia”. However as these towers shrink, the summer time stream of water within the Ganges and its tributaries is dwindling too.

People are making issues worse

The reckless extraction of groundwater is aggravating the state of affairs. The Ganges-Brahmaputra basin is without doubt one of the most quickly depleting aquifers on the earth, with water ranges falling by 15–20 millimeters every year. A lot of this groundwater is already contaminated with arsenic and fluoride, threatening each human well being and agriculture.

The position of human engineering can’t be ignored both. Tasks just like the Farakka Barrage in India have decreased dry-season flows into Bangladesh, making the land saltier and threatening the Sundarbans, the world’s largest mangrove forest. Selections to prioritise short-term financial features have undermined the river’s ecological well being.

Throughout northern Bangladesh and West Bengal, smaller rivers are already drying up in the summertime, leaving communities with out water for crops or livestock. The disappearance of those smaller tributaries is a harbinger of what might occur on a bigger scale if the Ganges itself continues its downward spiral. If nothing modifications, specialists warn that thousands and thousands of individuals throughout the basin might face extreme meals shortages throughout the subsequent few many years.

Saving the Ganges

The necessity for pressing, coordinated motion can’t be overstated. Piecemeal options won’t be sufficient. It’s time for a complete rethinking of how the river is managed.

That can imply lowering unsustainable extraction of groundwater so provides can recharge. It should imply environmental stream necessities to maintain sufficient water within the river for folks and ecosystems. And it’ll require improved local weather fashions that combine human pressures (irrigation and damming, for instance) with monsoon variability to information water coverage.

Transboundary cooperation can also be a should. India, Bangladesh and Nepal should do higher at sharing information, managing dams, and planning for local weather change. Worldwide funding and political agreements should deal with rivers just like the Ganges as international priorities. Above all, governance have to be inclusive, so native voices form river restoration efforts alongside scientists and policymakers.

The Ganges is greater than a river. It’s a lifeline, a sacred image, and a cornerstone of South Asian civilisation. However it’s drying quicker than ever earlier than, and the results of inaction are unthinkable. The time for warnings has handed. We should act now to make sure the Ganges continues to stream – not only for us, however for generations to return.

Mehebub Sahana, Leverhulme Early Profession Fellow, Geography, College of Manchester

This text is republished from The Dialog beneath a Artistic Commons license. Learn the unique article.